You give, I give, all must give.

— Enga proverb

This is a story about a unique tribe of people in Papua New Guinea. My information is based on the detailed book called Historical Vines, by American anthropologist Polly Wiessner and her Enga colleague, Akii Tomu. The reason Enga are of interest to the project of this blog are several. First, they are a large and successful tribe in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea, woven together by culture and language. Second, they have made oral history an important part of their heritage passed down in the men’s houses from generation to generation. There are reliable data going back to about 1650. And last, they have — within memory — moved from mostly hunter/gatherers supplementing with swidden gardens to largely horticultural/agricultural subsistence and trading economy based on introduced sweet potatoes, and pigs. At the same time, they transitioned from what might be termed egalitarian transegalitarianism to pronounced status and wealth differences while maintaining egalitarian ethos. The accompanying changes are described in detail by the various elders interviewed, through direct witness or cross-checked rememberance.

Enga settled in the Highlands of New Guinea as the glacial cover retreated and the climate warmed, many centuries ago. They hunted marsupials and cassowaries, gathered the nuts and greens of the forest, and grew taro in slash and burn gardens. Land was plentiful, and they lived in widely spread-out settlements. There is pollen evidence that at one point they made the decision to concentrate and intensify their taro gardens in the bottom lands, and let the forests regenerate. About 300 years ago, sweet potato made its way slowly from the lowlands, where it was an indifferent crop, to the highlands, where it came to produce so plentifully that it changed the course of Enga history. Originally, men hunted, women gathered, and men and women worked the gardens together, men clearing and planting and women tending and harvesting.

Much changed with the gradual introduction of the sweet potato which turned out to produce prodigious amount of food in this mountainous climate, surpluses became ridiculously easy to come by, and the pig was turned into sweet potato “storage on the hoof.” The women became the primary food producers, while the men began to devote more time to traveling, trading and politics. Populations grew, tensions increased between the “hunters” and the “farmers,” and fights for fertile land became more frequent… Today, all the land is taken.

The population in the early days is estimated at 10,000 plus. Recently, 110 tribes divided into many clans and subclans were documented by the study conducted from 1985-95, and by then the population burgeoned to over 200,000. There are 9 mutually intelligible dialects. The clans are thought of as patrilineal associations of equals, while kinship on the female side plays an important cultural role in opening the society up to wider cultural influences, facilitating exchange with in-laws and beyond. Land is owned both individually and by the clan. A man can pass his land to his descendants, but it cannot pass to anyone outside the clan, unless they become permanent members. Clans and tribes have a common origin myth, sometimes referring to immortal sky people, other times to animals. Genealogies play a large role in establishing inheritance rights to land.

The Enga province is blessed with 7 salt springs, and this salt provided a prime item for wide area trading. It was exchanged for high quality stone axes, shells, cosmetic oils, bark twine, and foodstuffs. The trading paths would in time play an important role in the spread of various cults, as well as the extensive Tee exchange (a carefully organized sequence of trade-based festivals) network.

Westerners began to make modest inroads in the late 1930s. Enga suffered severe epidemics post contact, but unlike other tribes, their population continued to rise, possibly because the Enga had a tradition of stringent quarantine for people afflicted with contagious disease. There’s been an emphasis on large families: sons to assure future strength of the clan, and daughters as producers and links for exchange networks outside of the clan. Until the last few decades, the division between the sexes was strengthened by the existence of separate men’s and women’s houses. Incipient big men were always — as far back as memories reach — found at the focal points of influence over the flow of goods and valuables.

Egalitarianism

Even in the hunting-gathering days, some men did rise to modest prominence on account of their oratory, hunting prowess, and able mediation of conflicts. This trend intensified as the Enga society grew in complexity. But egalitarianism was deeply rooted, and remained so until modern times.

Each adult in Enga society is a potential equal within gender and within the clan. Exceptions are granted to leaders who share their wealth with the clan. These leaders go to great lengths to show that what they want is also to the benefit of the tribe, while veiling self-interest from the public eye.

People are very careful not to boast about the accomplishment of relatives or ancestors; individual names in history are often replaced with clan names, and while individuals are credited, they are never elevated to the status of heroes. To the contrary, egalitarian ethics structure oral traditions to the point that founding ancestors may even be ridiculed. In the tribal “hall of fame” are such characters as Lungupini who uses his own leg as a block against which to cut grass. His and other ancestors’ exploits showing stupidity, tricksterism, and foolishness have entertained generations.

Among Enga, escalating competition is not practiced, where one loses if one does not give more than one has received. Generous returns for gifts given are desirable, but not necessary; they are aimed at strengthening the bond, not winning in the “game” of giving and establishing temporary superiority. Neither individuals nor clans try to outdo each other by giving back more than they received. Competition is constrained within the clan in other areas as well. For example, people do not compete to “be right” in the matters of history, but rather compare and correct the stories. This is not so unusual. Competition was severely constrained in many pre-state societies. If competition is allowed to accelerate, how would the emerging inequalities be mediated?

Cultural artifacts — myths, magic formulas, traditions, poems, songs, stories and proverbs — were all used not only to anchor one’s identity and to impart certain values, but also specifically to bring about change, or to mediate its effects.

Formerly, cults that specifically focused on rebalancing male and female energies were practiced with the intent to make peace between the sexes. Women are not equal in status to men, but are well respected as producers, and as diplomats behind the scenes. If a woman or child sickens or dies, the man has to make payments to the in-laws for the loss.

Employing men from one’s own clan would signal exploitation and inequality and would lead to loss of support. The big men only employed servants from among nearby clans, distant relations or immigrants. If a big man broke this rule, he would fast lose influence, because Enga understand that employment creates inferior positions. “Because fellow clansmen were equals, servants were almost always men from other clans who could not set up households on their own land — for instance war refugees, or the handicapped from inside or outside the clan who could not stand on their own. Blatant exploitation of one’s own clansmen, who were by definition equals, would eventually lead to loss of support.”

Cult duties were not part of big man repertoire; it was the elders or traveling hereditary shamen who were the specialists regarding cult ceremony and magic. Sons of low status men could become big men.

Kamongo

Even in the early days, big men — kamongo — are remembered to have risen to leadership. Small feasts based on taro and the produce of the forests were held, and people visited long distances. The pig did not play much of a role then. The kamongo were humble men who worked for the good of the tribe.

Even though the authors stress how durable and difficult to dislodge was the egalitarianism of the Enga clans, it is clear from the accounts describing the exploits of the succeeding generation of powerful kamongo that power indeed corrupts. Where the great grandfather was a modest man seeking to forge friendly relations with everyone, his son was a powerful wheeler-dealer who had many servants, great wealth, and put much emphasis on ceremonial attire and theatrical performance. His speeches stressed his abilities to deliver what he promised. The generation after him was already given to loud and shameless boasting and the insulting of competitors, and after that the kamongo began to lose respect for infighting, intrigue, cheating, heavy politicking, and political murder.

While egalitarian values were often stressed and catered to, nevertheless, greater and greater inequality crept in, tolerated because the kamongo divided much of his wealth among the people of his clan, or applied it to clan projects (wars, war reparations, cult purchases, increasingly ostentatious ceremonies). In addition to kamongo leaders, the Enga also had local clan elders, war leaders and hereditary ceremonial specialists.

Men had to campaign to be leaders. They campaigned by giving pigs or other things to those who needed them. They paid bridewealth for others. They became spokesmen for their clans during confrontations with other clans. They offered hospitality to strangers. Anything done to benefit or promote the clan would be regarded as part of their campaign for leadership. The people recognized men who did these things as big-men.

Here is a list of kamongo duties:

– mobilize work parties

– settle internal disputes

– distribute food at funerals

– provide group members with dress and ornaments for ceremonial occasions

– host traditional dances

– plan events

– conduct peace negotiations successfully

– orate elegantly in public

– know the skills of peacemaking oratory to restore balance by avoiding implications of superiority on either side

– help finance bridewealth and other obligations of clan members

– mobilize the clan to go out and get pigs for a Tee exchange

– manage and distribute wealth in the Tee exchange

– give special gifts to potential trouble makers in a reparation settlement

They preferentially offered or withheld finance, manipulated both the multiplicity of interpersonal relationships in any exchange situation and the ambiguities surrounding who the proper receivers would be, for his own and his group’s advantage. The kamongo is nothing if not a genius at devising intricate plans which seem to benefit everyone, including the persons who do not receive pigs, and then at convincing people to implement them.

Wars resulting from premeditated homicide, rape, or other aggressive and insulting acts were sometimes engineered by big-men as parts of strategies to attain their own political goals. Successful payback by the enemy tribe reestablished a balance of power, and enabled tribes to hold on to their territory.

Though Enga adults of the same sex are considered potentially equal, men can make names for themselves, become kamongo and wield considerable influence by displaying skills in mediation, in public oration, and in manipulating wealth, among other things. Competition for status and leadership in these arenas is intense. Tolerance for big-men’s having several wives, more wealth, and greater influence than others depends heavily on the benefits they provide to their fellow clan members; should they fail to deliver, their demise is rapid.

Cults

From the early generations onward, Enga was a society of long-distance travelers, traders, importers and exporters, innovators and experimenters venturing out on paths forged by marriage ties. New crops, cultivation techniques, goods, valuables, cults, and even styles of leadership were given and taken readily — but experimentally so. They were accepted into the current repertoire, placed side by side with existing heritage, and left to settle into their own niches over time.

Such openness also extended to the realm of ritual. New cults were readily purchased and added to the existing repertoire. For clans who had eight to twelve cults or healing rituals, the solution to competing possibilities was not to narrow the field by discarding some but to perform rites to determine which was appropriate for the problem at hand. The same held true for styles of leadership. The often flamboyant performers and orators who organized the Tee cycle and Great Wars did not replace the local clan leaders, though their roles overlapped. The value of both was recognized, the one to represent their clans in a larger political arena and the other to provide stability in internal affairs. And so the old continued to reproduce the cultural heritage of the past and provide continuity while the new kept abreast of change.

Cults for the ancestors were the anchors of society. In their performances, the ideal relationship between various tribal segments were acted out and central norms reaffirmed, particularly the equality of male tribal members and households and the obligation of group members to share and cooperate. Boundaries were opened and relatives from other clans and tribes came as invited guests to celebrate, bringing specialties from their areas to help provision the feasts. Cults were also exchanged widely among Enga and with neighboring linguistic groups; in this context they became important forums in which leaders could set new directions. As integrative events, ancestral cults grew hand in hand with economic developments and must be counted among the greatest systems of ceremonial exchange.

The authors mention how the recent disappearance of the cults due to missionary activity — while retaining and enlarging economic exchange — left the society unmoored, unable to maintain an equilibrium and harmony through the balance of ritual and exchange. Some of the cults were maintained by ritual experts, others by tribal elders and big men, to establish cooperation with the spirit world and its mysteries, harmony between the sexes, effective response to crises, and mediation of change. Ritual innovation and the purchase of cults created an eclectic and evolving mix of ritual, magic, initiation of young people, and cosmology.

Following Enga logic that “name” and prosperity stem from distribution rather than from retention, cults or elements of them were exchanged widely. Both importers and exporters stood to benefit by enhanced connections made possible by shared traditions. They believed that with proper ritual, the spirit world and human world need not work at cross purposes but could cooperate to bring about prosperity. Ritual celebrations also brought about moratoria on warfare. At the more egalitarian, unity-building ritual celebrations, food was provided free for all. Some of the surplus was simply channeled into communing with the ancestors, and curtailed competition.

The cults were manipulated to set new goals and values, regulate relations between generations and genders, and standardize beliefs to make wide area exchange and marriage alliances. Bachelor cults helped young men mature, develop their individual abilities, and overcome the inequalities of birth and background. In particular, they were led to develop an aura about them — posture, movement, speech, and assurance — signaling physical health, inner worth, and social effectiveness. Such a man would then be able to gain the cooperation and generosity of others. Eventually, wealth management was added to these virtues by the leaders bent on extending the networks of exchange ever further. Bachelor cults and initiation ceremonies strengthened the bonds of brotherhood and the chance of future consensus. It also gave the older generation more power to steer the younger one.

The cults provided a counterpoint of opposing ideals — ones of equality, sharing and cooperation within and across boundaries that limited or structured the growing competition. They rewove the fabric of society when it was torn by competition, in order to reestablish continuity and balance in relation to the past, for the present, and to lead into the future.

Each cult was different. To give you the flavor of it, one of the cults — the Kepele cult — focused on building the structure — the house — around which the ceremonies would take place. Several clans collaborated, each having part of the building process as their task. The ritual would include processions as well as specific magical procedures meant to bring to fertility to the tribe, promote cooperation and good relations, and reaffirm the values the tribe depended on. Every household was expected to bring one pig, and the food was free to all.

Ceremonial Wars and the Tee

The Enga engaged in real (destructive) wars, usually over territory after population had grown. But they also staged so-called “ceremonial wars.” Young warriors were hosted by certain clans, strategic skirmishes went on by day, and feasting, dancing and courting followed at night. Spectators came from far and wide. Casualties were few, and after the war had ended, war reparations for the 2 – 4 men slain among allied clans would be undertaken. These reparations were not for lives lost, but rather for the contribution the dead man would have made. As such, they went on for years. In later times, reparations to enemies became common as well, because enemies no longer could just move on to empty territory — you were still neighbors and had to get along in the future. Reparations also prevented destructive feuds. Some elders believe that the Great Wars provided an outlet for aggression and that in total fewer lives were lost overall. The Ceremonial Wars were a brilliant invention that induced people to produce huge surpluses that grew the economy. It also provided new opportunities for creating new trading and marriage connections. They were, in effect, tournaments, carefully arranged and fought to display military strength, form alliances, and cultivate exchange.

The common cause, danger, and spectacle drew unprecedented crowds. Owing to the sheer number of participants brought together by the ever better drama and ritual, the Ceremonial Wars were instrumental in constructing vast exchange networks fueled by intensified home production within a broad segment of the population. The glamour, excitement, group spirit, and ceremony of these great tournaments lent much greater social and symbolic value to pigs, mobilizing each and every household to step up production for the exchanges. Basically, the Enga used the cults, the ceremonial wars, and later the famous Tee exchanges all to crank out surpluses and pass the new wealth around.

Tee exchanges were held for the principal reason of paying back creditors. They were also public distributions of wealth for specific events: marriages, funerals, and war reparations. When a project needed financing, a Tee would be organized. Those who wanted to join would arrange marriages to those along the routes, and began sending wealth into the system; eventually they would receive returns from it.

In order to join the Tee, families had to step up production. Early on, only a few families chose to do so. Many people had only a few pigs, and were not interested in the labor-intensive task of raising more. Only later, as the Tee came to be flooded with wealth from the ceremonial wars and then new wealth introduced by the Europeans and became more visible, did many more families join.

In the end, though, the Tee began to fall apart: partly, the kamongo became corrupt, endless conflicts tore the organization apart, and women objected to yet another step up in production.

The Tee comprised of the chains of finance that tapped into the wealth of non-kin; greater access to wealth was compelling to the neighbors who heard about it and then sought to join, while big men sought new sources of influence and finance to control the trade. Altered values and intergroup competition were needed to develop the system further.

It was constructed by a few individuals along major trade routes who discreetly concatenated preexisting trade and exchange relationships into chains of finance. The early Tee allowed big men to assemble more wealth without greatly augmenting production or arousing the attention of fellow clansmen. Competition to control the flow of wealth was there, but merely as a current that ran under the surface.

And now?

One of the last great kamongo gave up the pigs and converted to Seventh Day Adventism, as did many others. Nowadays, it’s Islam that draws the young. And the tribal traditions are fading away.

Enga who had experienced precontact years as adults described them as a time when people sought ever new ways to keep abreast of change, maintaining equilibrium and harmony through exchange and ritual. Balance was tenuous, however, for ever-accelerating production for exchange depended on a generous environment. Should exchange or ritual fail, warfare was by no means muted but alive and well-practiced as an alternative solution. And the environment could not be infinitely generous. In the face of growing pig and human populations, a time would come when resources would be insufficient for all. Choices then would be more severely constrained by the natural environment. As it happened, Australian patrols marched into Enga in 1939 to set off an entirely different trajectory of development… But one is tempted to ask, had the patrols not marched into Enga, what then?

Could the inventive Enga have come up with a solution that has evaded humans elsewhere?

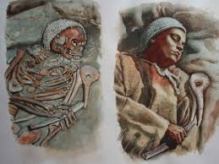

Enga in ceremonial dress