The Neolithic revolution was neither Neolithic, nor a revolution.

— Colin Tudge

Human beings of the race that calls itself Homo sapiens lived in relative equality, in small foraging bands all its existence from the time they emerged about 200,000 years ago. Then, around 30,000 years ago, during a bit more clement time within the last ice age, glimmerings of inequality arose at sites known in Europe — in places that were unusually plentiful in game.

Tools grew more elaborate, trade widened, grave goods accompanied certain burials, jewelry and other prestige items became notable, and evidence of control over significant labor was in evidence (viz, for example, the stupendous numbers of sewn-on ivory beads in the Sungir graves).

It has been hypothesized that at some locations, the fabled painted caves in France and Spain turned into places where elite children underwent their initiations. But when game grew sparse, humans went back to tight egalitarian cooperation.

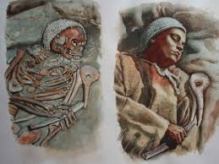

Significant inequality kicked off around 15,000 years ago, after the end of the ice age, during the Magdalenian culture. By now, the dog, horse, and possibly the reindeer had been tamed by these stone-age foragers, thousands of years before the domestication of plants. The delicious pig was bred, also by foragers, in Anatolia about 13,000 years ago, while their Syrian neighbors may have tinkered with rye. A couple of millennia later, foragers built the impressive ceremonial center of Göbekli Tepe which shows the command of vast labor pools, not only to build the center, but eventually to bury it under a hill of gravel.

While most of the tribes roaming the Earth continued in the age-old foraging and sharing patterns, a few cultures blessed with particularly fecund landbase began to amass wild surpluses, captured or tamed animals to use in ceremonies, processions and sacrificial rites, threw elaborate feasts, forged far-reaching alliances and trade, and started the engine of ratcheting economic growth, which then — very slowly and haltingly at first — began its world conquest.

The “feasting model theory” for the origin or agriculture was proposed by archeologist Bryan Hayden. It posits that intensive agriculture was the necessary result of ostentatious displays of power. To regularly throw feasts as a means of exerting dominance, large quantities of food had to be assembled. The enterprising Big Men came to be admired and encouraged for their charisma and skill in wheeling and dealing as they organized these ever larger, more sumptuous and more competitive affairs.

As feasts and ceremonies got more lavish and impressive, the economic treadmill speeded up. People were propelled to get inventive. Foragers had tended wild plants since time immemorial; now they began to cultivate more. Not to feed themselves day-to-day, you understand: for that, they had the plentiful wild food all around them that had always fed them. But the aggrandizive feasts demanded delicacies and amazing new foods to impress the guests. The animals, of course, were the first coup. The dog, whose genome began to diverge from wolves 100,000 years ago, was already domesticated 36,000 years ago. How impressive it must have seemed to have a tame wolf at one’s side who could keep the wild wolves at bay! And so, later, much more effort was put into making a steady supply of animals available for processions, ritual sacrifice, and feasting.

The first domesticated plants were a curiosity. Cultivated rice was proudly presented by the elites at feasts and glorified in myth. But the plant itself was fickle, produced little, and required a lot of work. For real food, people relied on manioc and wild staples; to impress guests or to trade for desired items, they used rice. And of course, rice and the other grains produced alcohol, another coveted item at feast-time.

The picture I see is not of late Paleolithic and early Neolithic people planting fields of grains and vegetables. I see them growing small experimental plots of plants that could be leveraged into prestige and wealth. In our age, people of modest means tinker in their garages and dream of making it big. The foragers tinkered in their small garden plots. Once an experiment seemed promising, it was given a bit more land, and began to be displayed at the table of a few chosen people, not unlike Wes Jackson showcases his latest, most promising perennial grains at the Land Institute’s yearly festival, and gives small amounts to his friends and allies to try out.

It took many centuries, perhaps millennia, of such small-scale experimentation for grains, lentils, and other cultivars to achieve some reasonable production standard. Only then did they make sense as staples. What were once luxury foods became common fare. And once the old luxury foods were no longer scarce, new prestigious luxury foods had to be found for the insatiable elites. What are some of those early luxury foods? Chiles, vanilla, avocados, gourds, chocolate, alcohol, pork. The grains rice, rye, wheat, barley and maize were all accorded special respect and sometimes even divinity. A big coup was scored when the enormous and dangerous aurochsen were turned into smaller docile cattle.

And so the engine set to crank out more and more nifty foods began to crank out more people, and the Food Race kicked off in earnest. Tractable animals and improved plants were only some of the items the elites and their socio-economic treadmill pressed for. The others were metals, better tools and containers, more elaborate houses, monuments, ornaments and rare items from faraway places. Bridewealth, debt, invented genealogies, new twists on old stories, and other cultural artifacts validated the new extractive unequal economy. Thus began the endless stream of innovation and profusion of goods whose tail end we are experiencing now, supported by the geysers of fossilized fluids from the bowels of the earth.

the Seated Goddess

Wild foods were the staples at Çatal Hüyük, the first town. It was wild grains that were venerated and interred in the statuette of the Seated Goddess. Wild aurochs bucrania adorned the walls. And the people ranged for miles to gather and hunt, rounding up wild goats and sheep into adjacent corrals. But I wager they had tiny garden plots nearby on the rich alluvial and regularly flooding soil surrounding their hillock, plots where they experimented with small amounts of exotic foodstuffs emerging from their patient manipulation. It would be thousands of years for the results of some of these trials to become widespread. Tinkering was so uncertain and laborious! The plentiful foraging grounds that surrounded them made such leisurely experimentation possible.

When their later descendants tried to grow the much improved crops in ever larger quantities, they ran into a problem, damaging the soil they were forcing past endurance and eventually causing crashes all around the Levant and Mesopotamia. These crashes were not really caused by ignorance — our clever and observant ancestors were savvy to the ways of the land — but the inexorable treadmill pushed and pushed them so they pushed and pushed the land, until it collapsed. Then they starved or migrated, taking their destructive system with them.

This ratchet, friends, is the socio-economic origin of agriculture as we know it. It is also the origin of destructive mining and metallurgy, of despotism, loss of leisure and increasingly debilitating work, increasingly violent conflict, population explosion, and slavery. In other words, agriculture turned destructive not because of some intrinsic flaw within larger-scale, more sophisticated cultivation. It turned destructive for the same reason mining, conflict, grazing, or governance turned destructive. Stay tuned.

March 12, 2015 at 8:53 am

So the world is now just one big potlatch?

March 12, 2015 at 9:05 am

Heh. I guess that’s it, Brutus! 🙂 I call it the cult of MORE.

March 12, 2015 at 1:49 pm

Yeah, MORE is the problem.

I wish I could figure out how to get people to enough. I guess that’s the point of pulling the plug.

I’m interested to seeing where you go with this–it seems like you are building the history of the ‘treadmill’.

March 12, 2015 at 4:46 pm

Oh you gotta see this! A short vid! Lord Man.

So apropos (the cult of MORE).

This vid will go viral. And it’s soooo beautiful!

MoonRaven, I am coming to a place where I think I can put together the whole sequence of “WTF happened?!” that I have been working out for about 8 years now. I want to see what sort of a fulcrum it offers in our predicament. It’s almost cohered in my head. I am not really an econ-thinker (econ gives me a headache) but I might have more to say about the cult of MORE. There are better heads than mine that can go deeper with that.

March 13, 2015 at 2:37 pm

The aggrandizer personality is central to this thesis, and while I would not deny that such a human type exists (in fact, this practically defines most Americans), I would suggest that among immediate-return hunting and gathering groups, great pains were taken to deflate such egotists and keep the mobile group strictly egalitarian. (See especially, David Boehm, Moral Origins: the Evolution of Virtue, Altruism, and Shame). Once we got into food storage among delayed-return hunter-gatherers, whoever controlled the food developed more power than others, and the long slide toward stratification, hierarchy, and patriarchy was inching its way into human life. An article that might be of interest in this regard is, ‘Co-evolution of Farming and Private Property during the early Holocene,’ by Bowles and Choi, [full text] where they find that the early farmers were evidently of this same aggrandizing type. They theorize that many of these types must have gotten together in a pact of mutual defense, in order to protect their crops from their own people, who still held the ethic of sharing with the group.

It is not perfectly clear to me, Vera, where you come down on Nature-Nurture thing. Are these aggrandizers genetically determined, or are they the products of culture?

I found your use of the word ‘system’ quite interesting. In my own researches of the past couple years, I kept coming back to the human entanglement in complex systems; systems that have imperatives and agendas of their own; systems that end up leading around by the nose; systems that are traps we cannot free ourselves from, and are now leading to planetary collapse.

It seems to me, Vera, that you have a bias in favor of agriculture, and that you continue to absolve agriculture from its central role in our decline and fall. I think it is right in the big middle of our muddle. It doesn’t stand alone, but any way you slice it, it is a necessary ingredient to the untenable world we built on its back.

March 13, 2015 at 6:07 pm

Lots of good points, wildearthman. Before we get into the meat of the discussion, I occurs to me to define aggrandizers here. (They are definitely not most Americans. 🙂

As Hayden says, these are people of whom a few occur in any population. As you point out, egalitarian foragers were at pains to place stringent limits on them. They strive to promote their self-interest over the interests of others whenever the opportunity presents itself. Hayden thinks that they occur because evolutionary speaking, too much altruism can be detrimental to the survival of a group. Then he says: “Aggrandizers use any pretext to push people into producing more and more surpluses as well as relinquishing some control over their goods to the aggrandizers who organize these purportedly beneficial events. They gravitate toward the roles of big men, chiefs, elites, businessmen, and politicians. They aggressively promote changes in society that are in their own self-interest. In extreme cases, they are aggressive, ambitious, acquisitive, accumulative, adversarial and adventurous. I call them ‘triple-A’ personality types.”

Now, off to read that article.

March 14, 2015 at 6:31 am

Wildearthman – Hayden sees it the aggrandizers as genetic. I looked at it from a nurture point of view and see it as a continuum. http://sunweber.blogspot.com/2014/11/the-aggrandizer-personality-nature-and.html

I wonder if there is not an element of “unfolding” cultural/social evolution that doesn’t take place with the aggregation of surplus. It might best be called devolution because perhaps in the accumulation of wealth/power the shaping of the individual moves away from a balance of cooperation/competition to the development of narcissistic and Machiavellian personalities. So the collapse is a product of success. Or is that what everyone is saying and I am late to the party.

Vera – another good one. You and Wildearthman, why are you chasing this information? Not criticism, just curiosity.

March 14, 2015 at 10:33 am

I too see the aggrandizers as genetic, though on a continuum… and somewhat modifiable through upbringing and tribal norms. In the days of the generalized foragers, the worst of these were offed or chased off, and the rest learned to behave.

Yeah, surplus plays a big role in the ratchet, of course. In fact, the only reason ag can in fact be vilified for those so inclined is that without it, we’d just have the sort of smallish despots, war, slavery and potlatches that were prevalent out in the NW, in BC and surrounding areas. A rich foraging economy produced the evils that Jared Diamond talks about too. They just could not quite get out of hand as agriculturists could.

I have been chasing this information for 8 years now… since I saw Diamond’s essay. I bought his argument then. Then I decided to look further. And decided it just does not add up. This essay is — I hope — the last part of the argument.

Oh and about my bias: it is for regenerative ag in combination with foraging; in my personal utopia, it would be maybe 50/50.

March 14, 2015 at 12:25 pm

Vera – Perhaps my thinking of the matter is clearer now. Not necessarily correct.

Hayden sees the aggrandizers as genetic. Perhaps the original manifestation of the aggrandizer (psychopath) was genetic and needed the surplus to undermine suppression and allow expression. I wonder if with the growth of wealth and power as well as population if the child rearing practices of the ensuing societies don’t shape generations that are ultimately the instruments of their own demise?

It might best be called devolution. Perhaps in the accumulation of wealth and power the shaping of the individual moves away from a balance of cooperation/competition to the development of narcissistic and Machiavellian personalities. With the increases in numbers, these personality types become a larger percentage of the population.

In a global population of seven billion, there are simply countless niches for the practice of accumulation of power via manipulation.

The formation of aggrandizers resists modification or constraint. The global economics and the global political interplays dictate consumption and consumerism to maintain the power of the elite. This promotes a world of mini-aggrandizers or mimickers.

So the collapse is a product of success.

March 14, 2015 at 1:02 pm

So wildearthman, I read the article. Interesting. They do admit that food storage existed prior to the advent of farming (I myself would speak of the very gradual incorporation of horticulture and grazing into forager economies), and they also very briefly admit that privatization existed in rich forager economies. On the other hand, they never mention the fact that many places (e.g N. America) public storage existed well into colonial days, where anyone could come and help themselves from the public granary, even passing travelers.

Privatization of storage. I see it as an aggrandizer strategy, just like privatization of choice fishing holes. Note, also, that the authors of the article call free riders those of the tribe who raid a would-be farmer’s rice paddy and share the rice all around; while not calling the rice farmer a free rider despite the fact that he was the one who went (in contravention of custom): “this chunk of land is mine and mine alone, and nobody else can pick its products.” Wasn’t this would be farmer free riding on the commons that belonged to the tribe, just as the 17th century English lords free rided on the commons in the Enclosures?

Anyways… I don’t dispute their claim that for agriculture coevolved with privatization. But maybe if it hadn’t, it never would have become quite so destructive. And they never quite explain why people who were so disadvantaged by switching to agriculture that their nutrition plummeted, they shrank in stature, and generally failed to thrive for 8 centuries — how the heck did they survive? They said they outbred the others because they were sedentary. Hard to believe that they would outbreed anyone, particularly since many foragers/minor horticulturists would have had the same advantage, of being mostly settled, or at least semi-settled.

Sorry about rambling. Well, tell us now what you see in this article that provides a counter-point to the theory I have presented?

March 14, 2015 at 1:08 pm

John, yes, the collapse is the product of their success. But in game theory, what you often see is predatory edge populations making their inroads more and more, but eventually some sort of threshold is crossed and the cooperators begin gaining on them in turn. Possibly because a social ecology with too many predators and too few prey spells doom to the predator. We can only hope.

March 14, 2015 at 6:07 pm

[…] How agriculture grew on us […]

March 16, 2015 at 11:01 pm

I thought I was supposed to be getting emails to let me know that someone had responded to a post I was following–but I never did. I found your reply accidentally after publishing a new post on my blog. I’ll have to give some thought to a response now that I know we are in a conversation.

March 17, 2015 at 2:59 pm

I double checked, and you should’ve. WordPress sometimes malfunctions, I am afraid. Looking forward to your thoughts.

March 17, 2015 at 9:40 pm

When I look at history and pre-history I see a huge discontinuity, in terms of survival strategies, and I like to paint a bright line between the two. In real life, this discontinuity took time to develop, and there have been some hybrids along the way, but none of this messiness alters the sharp contrast between living in the Gift and living in the Theft. The hunter-gatherer thrived within the context of fully functional, intact ecosystems, and his survival strategy was to do whatever he could to keep his chosen territorial systems whole and in dynamic balance. I’ve noticed that people’s behavior is very much influenced by incentives, and the overriding incentive for people who make seasonal rounds following the ripenings and migrations of the food sources they gather and hunt is to take good care of their territory. From a systems point of view, and from a moral point of view, this is a durable land ethic, because it is based on the truth that all flourishing is mutual, and it allows all citizens within the Community of Life—no matter how humble or imposing—their place within the Life System. For each and all, including the human, this is living in the Gift.

Living in the Theft is a different proposition entirely. Instead of living off the interest of Nature’s bounty, this way of life fattens and stores up riches by living off Nature’s principal. This means spending down nearly four billion years of accrued biological and geological complexity, diversity, and resilience, and doing so at an ever-accelerating spendthrift pace. A death-wish and madness is built into this model, and the madness poisons the human heart and mind with an intensity that matches our poisoning and plunder of the planet. We have told ourselves the Big Lie that we are separate from Nature—this lie that has authorized and validated our theft, enslavement, and murder of a living planet—but we are not separate; we are native to this planet, and the deeper part of our being knows this, and feels the cognitive dissonance of living a lie.

I think it is important to understand that agriculture and private property, working synergistically, set in motion a parade of evils that would have been impossible at the scale of the hunter-gatherer. When you change scales from simple to complex something terrible happens: complex systems take over and humans lose control of their lives. Living in the Gift, within the annual solar budget, and dependent upon fully functional ecosystems, human can only get into just so much mischief. And I would include here what Lewis Mumford calls democratic technics. As long as you are at the technological level where everyone makes their baskets and arrows and bows, egalitarianism can still thrive. Once you start having hierarchy, with bosses and workers, you have crossed over into authoritarian technics—and lost control of your life.

There is more to my rationale, but this offers a sketchy outline. To me, it is not particularly relevant that our species showed some undesirable characteristics before the Neolithic Revolution, because none of these were the turning point. The crucial fork in the path that would seal our fates was agriculture and private property combined—and what these inevitably led to. As I see it, the human is easily tempted by Power, such as the power promised by complex systems. But once we have taken the bait, we find we are in a trap—a trap that we have yet to figure out how to escape. As humble citizens of the World’s Community of Life, we could live here for millions of years (very probably). But humility is not our strong suit, so, full of ourselves, we will go down in a blaze of gory glory, taking most of the living world down with us.

March 17, 2015 at 9:41 pm

Still no email notifications.

March 18, 2015 at 11:03 am

Please try this: make a test comment, and at the bottom, there is a box that says, do you want notifications to the comment. Check it and I will respond and we’ll see if it works. If not, I will contact wordpress. Thanks!

March 18, 2015 at 9:00 pm

Very well put, wildearthman. I guess where my narrative differs is that living in the Theft began among the complex hunter-gatherers. That is where the fateful turn occurred. I have no disagreement that once they ironed out the bugs in large scale cultivation and it took off, the stupendous surpluses fed the monstrous system unlike what could have happened with hunting-gathering.

Also, keep in mind that the Australian aborigines did tremendous damage to land and climate with vast fires, prior to Ice Age Maximum. Were they living in the Gift, you’d say?

Good points about the authoritarian technics. Now, temptation to Power… that, methinks, is where the turning lay. I agree that’s where the trap was sprung.

March 19, 2015 at 9:52 am

It would seem that the conditions for the ruination of the world were always there, just waiting for the right species to come along and spring the trap. Somehow this view always gives a migraine of consternation. I would have thought the Life Force would be more protective of her 3.8 billion year Project of Life. And in fact I am still hoping she will intervene before the ruin is complete.

March 19, 2015 at 9:54 am

I think checking the box might be the key!

March 19, 2015 at 10:59 am

So let’s see if it works. Here goes. 🙂

March 19, 2015 at 11:02 am

“And in fact I am still hoping she will intervene before the ruin is complete.”

I am counting on it. She is still giving us a chance. The odds are crappy, but then, odds aren’t everything.

March 22, 2015 at 8:19 am

A good description of how traditional peoples dealt with self-aggrandizing personality types is given in this article from Slate, Ayn rand versus the Pygmies:

…When no one was looking, Cephu slipped away to set up his own net in front of the others. “In this way he caught the first of the animals fleeing from the beaters,” explained Turnbull in his book The Forest People, “but he had not been able to retreat before he was discovered.” Word spread among camp members that Cephu had been trying to steal meat from the tribe, and a consensus quickly developed that he should answer for this crime.

At an impromptu trial, Cephu defended himself with arguments for individual initiative and personal responsibility. “He felt he deserved a better place in the line of nets,” Turnbull wrote. “After all, was he not an important man, a chief, in fact, of his own band?” But if that were the case, replied a respected member of the camp, Cephu should leave and never return. The Mbuti have no chiefs, they are a society of equals in which redistribution governs everyone’s livelihood. The rest of the camp sat in silent agreement.

Faced with banishment, a punishment nearly equivalent to a death sentence, Cephu relented. “He apologized profusely,” Turnbull wrote, “and said that in any case he would hand over all the meat.” This ended the matter, and members of the group pulled chunks of meat from Cephu’s basket. He clutched his stomach and moaned, begging that he be left with something to eat. The others merely laughed and walked away with their pound of flesh. Like the mythical figure Atlas from Greek antiquity, condemned by vindictive gods to carry the world on his shoulders for all eternity, Cephu was bound to support the tribe whether he chose to or not.

I find the discussion of whether these traits are environmental or genetic fascinating in lieu of the new research just out this week that there was a genetic bottleneck only in the Y-chromosome (not the X chromosome) that coincided pretty much exactly with the rise of agriculture:

Wealth and power may have played a stronger role than ‘survival of the fittest’

http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2015-03/asu-wap031615.php

8,000 Years Ago, 17 Women Reproduced for Every One Man

http://www.psmag.com/nature-and-technology/17-to-1-reproductive-success

For a timeline reference:

Ancient Britons Imported Einkorn Wheat 8,000 Years Ago, Say Archaeologists

http://www.sci-news.com/archaeology/science-ancient-britons-einkorn-wheat-02546.html

From this study, I think it’s clear that a small group of the most selfish, controlling, narcissistic, sociopathic and greedy alpha males monopolized access to the women, and thus were the only ones who were able to reproduce after the introduction of agriculture. Men less obsessed with status, power and control were “culled” from the gene pool, a process which has continued ever since.

This seems to indicate that civilization itself had an effect on our genetics that is self-reproducing. It allowed only the most ruthless males to survive. Indeed, this is what we see in ancient times where instead of most people having children, most men were evolutionary dead-ends: slaves, servants, worker drones, eunuchs, soldiers; while rulers had access to harems of hundreds or even thousands of women (unlike foragers or nomads). This is still roughly the model of the Middle East today, and probably one of the reasons it’s so violent and dysfunctional.

Our Western notion that notion that most men will form families is extremely recent. Even in the West, the notion was that men could not form a family until they could “afford” to do so. That is, unless you could claw enough wealth from the impersonal market you could not reproduce, and indeed many men remained bachelors their whole lives even up until the eighteenth century and beyond (compare the number of children of the servants with the aristocrats on Downton Abbey). The Kings, princes, generals, merchants and industrialists were the ones with the most surviving offspring. This would also select for the most greedy, dominant, exploitative and work-obsessed males, while culling people with other values and personality types.

So instead of putting people like Cephu in their place, people like him have been the only ones allowed to reproduce for the past 10,000 years or so (I’m exaggerating a bit here, obviously).

March 22, 2015 at 12:08 pm

Welcome, CH! This story (Cephu) is also showcased in C. Boehm’s stuff on the evolution of morality, called Moral Origins. He is big into gossip too as a way to weigh people’s behavior and maintain the norms of the group.

Thanks for the wealth of links, will be working through them. (Poor Ayn Rand, she’s become quite the whipping girl for all and sundry.)

November 23, 2017 at 3:09 pm

[…] How agriculture grew on us (Leaving Babylon) […]

January 4, 2018 at 10:48 am

[…] How agriculture grew on us (Leaving Babylon) […]